In 1958, in Montreux, Switzerland, a man in his late fifties died of lung cancer. In his later life he had loved BBC Radio’s “Goon Show”, and his family had often seen him double up laughing at its anarchic humour. After his death, his ashes were scattered on the summit of Cross Craigs, near Fortingall in Perthshire – although he had been born in India he was Scottish by his family heritage. His name was Douglas Jardine, and he is one of my sporting heroes.

D R Jardine, captain of England 1931 to 1934,

An amateur player who had to earn his keep

outside cricket, an outstanding if cautious batsman,

and a man of steel in captaincy.

On 14th January 1933 at the Adelaide Oval in Australia, Jardine’s men were in the field. Harold Larwood, possibly the world’s fastest bowler at the time, bowled to the Australian captain Bill Woodfull. The delivery was fast, banged hard into the track, and rose up at Woodfull’s body. Woodfull ducked under it, but somehow the ball was deflected from his bat into his body and he was struck a painful blow under the heart. He remained doubled up in pain for several minutes.

Larwood to Woodfull with a conventional field setting –

no “leg trap” of fielders.

The ground went quiet, no one on the field spoke, and then hoots and jeers came from some of the Australian spectators, angered at the aggressive bowling tactics. The verbal abuse rose in intensity. What then happened on the pitch? Did Larwood look at Woodfull in pain, and was there something in his eyes or in his body language which betrayed a moment of doubt about how he was being asked to bowl? Did Jardine, the captain to whom he was devoted and whom he admired so much, catch sight of this and feel the need to steady the nerves of his fastest bowler? Did he think to himself, “This is my responsibility. I won’t let anyone else carry the can.”?

“Well bowled, Harold.” He said, loud enough to be heard off the pitch.

With that remark he earned the hatred of the Australian spectators and a bogeyman status with Australian cricket fans which has lasted since then. But the encouragement made sure that Larwood continued to bowl as he, his captain, wanted him to. He could not have done it any other way. He could not have said nothing, thereby letting Larwood bowl without conviction. He could not have gone and have a quiet word with him – a “quiet word” was how a captain remonstrates with one of his team on the field. Encouragement is given out loud. Larwood’s intimidating bowling was exactly what Jardine had asked for, so Jardine took the responsibility upon himself and told Larwood “well bowled”.

Jardine was not out to be Mr Nice Guy in any case. He famously said: “I’ve not traveled six thousand miles to make friends – I’m here to win the Ashes”. This was in a period where batsmen, particularly Australian batsmen, and particularly the man who was arguably the greatest batsman of all time, Don Bradman, dominated the First Class game.

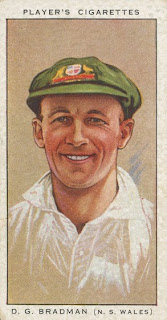

D G Bradman, New South Wales and Australia

Prior to the Ashes tour of 1932-33, Bradman’s batting average was almost one hundred runs per individual innings, a phenomenal performance. He was a player of classic strokes “all round the clock”. It was Percy Fender, captain of Surrey CCC who alerted Jardine to a weakness in Bradman.

P G H Fender, Surrey and England

Fender had spotted Bradman flinching away from one or two fast deliveries where the ball had reared up at him. Jardine decided that the only way to attack Bradman’s batting average was to attack this weakness. To do this he used a bowling strategy made up of elements already known in cricket – fast bowling, bouncers, “leg theory” bowling, setting a cordon of fielders close in on the leg side. It was called “fast leg theory”. Jardine didn’t invent it. It had been used to a certain extent before the 32-33 tour, although not with such consistency as Jardine decided upon. At the time none of the elements were against the laws of cricket, neither was fast leg-side bowling itself.

To carry out this strategy, Jardine called on two Nottinghamshire fast bowlers, Bill Voce and Harold Larwood, and the trap was sprung.

W Voce, Nottinghamshire and England

H Larwood, Nottinghamshire and England

Not everyone in the England team liked the idea. HH The Nawab of Pataudi disapproved, as did the vice-captain Bob Wyatt – although the latter made full use of it in a curtain-raiser match against an Australian XI in which Jardine did not play. Such was the loyalty that the steely Jardine inspired, however, none of his team criticized him in public. Australia hated “fast leg theory” bowling passionately, hated its deliberately aggressive and intimidating nature, hated the fact that it appeared to be aimed directly at the batsman’s body. A hostile Australian press called it “bodyline” bowling – the name stuck, and it was a byword in Australia for unsportsmanlike behaviour ever since.

It was aimed at the batsman, no question. It was deliberate, and it was ugly to watch, particularly if one had come to watch classic batting. It was designed to provoke one of three reactions in a batsman: firstly to evade it, or secondly to try to fend it off and risk being caught by one of the close fielders, or thirdly to try a rash shot. Bradman lost his nerve in the face of it; but having said that, his average for the series was still respectable despite being dismissed in one innings, first ball, by Bill Bowes, as he tried to hook a non-bodyline delivery. Other batsmen, however, didn’t. Another New-South-Waleser, Stan McCabe, simply took it on. He stood up to it and hooked the ball, making an outstanding innings of 187 not out in the First Test (in which Bradman did not play).

Another batsman who faced and dealt successfully with bodyline bowling was Jardine himself. In 1933 he faced the West Indies’ fast bowlers Learie Constantine and Manny Martindale. Martindale was about as fast and aggressive a bowler as Larwood. Jardine even hogged the bowling to save a colleague who was making heavy weather of it, and finished with an individual 127 runs. Jardine could take it as well as he could dish it out.

E A Martindale, Barbados and West Indies

Jardine’s uncompromising captaincy inspired later skippers such as Australia’s 1971-75 captain Ian Chappell and England’s 1999-2003 captain Nasser Hussain. He is one of Chappell’s Top Ten Ashes captains – here’s what Ian recently had to say about him:

“Jardine was a really smart captain. If you want to encapsulate what Test cricket is all about, just look at what Jardine did. The opposing player who was devastating all the opposition was Don Bradman. Bradman at that stage had an average of about a hundred. So what Jardine decided to do was to try to cut his average down. If you want to increase your chances of winning in a Test Series, you’ve got to try and disrupt the averages of the best players in the opposition. If you do that you increase your chances of winning – and that’s what Jardine did… I’ve always looked upon Jardine as a very smart captain and obviously a very good captain.”

Here is what some of his contemporaries said of him:

Pelham Warner (Middlesex and England. Tour Manager of the 33-32 tour): “If ever there was a cricket match between England and the rest of the world, and the fate of England depended upon the result, I would pick Jardine as England Captain every time."

Bill Bowes (Yorkshire and England): “To me and every member of the 1932-33 MCC side in Australia, Douglas Jardine was the greatest captain England ever had. A great fighter, a grand friend and an unforgiving enemy.”

Sir Jack Hobbs (Surrey and England): “He was a great batsman – how great I do not think we quite appreciated at the time.”

Could Douglas Jardine have done anything differently? At the time he led the Ashes Tour to Australia he had already had bad experiences in Australia and was not well-liked there. They had started in 1928 when a crowd of spectators began to barrack him about his Oxford “Harlequin cap”. He may have played up to it a little, but it was not long before the joke wore thin, and he came to the conclusion that Australian cricket spectators were boorish, unmannerly, and uneducated. The BBC’s Peter White suggests that as Jardine was known to have a sense of humour, he could perhaps have introduced a little of that into his on-field demeanour. But privately Jardine was painfully shy. He conquered much of that to become the man-of-steel that the team he led knew. However, there was a huge culture gap between him and the Australian crowd, a parcel of attitudes and misunderstandings which was never bridged either way.

It is not for provocative or partisan reasons that Jardine is one of my heroes – after all, not only he and Larwood are heroes of mine, but also Bradman and McCabe. I think it was that I was brought up in a cricket-loving family, first of all, and as a result of that I came to appreciate what made Jardine tick. I have always felt that posterity has been harsh to him, and I salute him as – if nothing else – a fellow Scot.

___________________

Postscript:

I have this to say, in fairness, to the Australian cricketers of the day. Though the hostile press called for retaliation in kind, the Australian team refused to do so. They regarded fast leg theory bowling as unsporting, and they stuck to that principle, though it might have cost them the Ashes.

One bowler the press suggested was Eddie Gilbert, the fast bowler from Queensland. Eddie was an Aborigine, only the second Aborigine to play First Class cricket. He was phenomenally fast, easily the equal of Larwood if not faster, and in 1931 had famously dismissed Bradman for a duck. Also, in a non-Test match during the 32-33 tour, he had struck Jardine and left a bruise the size of a saucer. Jardine was no stranger himself to getting hit by a cricket ball!

Eddie Gilbert never played for Australia, most likely because his bowling action was considered suspect by some umpires.